**Why Making ‘The White Album’ Was George Harrison’s “Most Depressing” Period in The Beatles

When The Beatles released their sprawling 1968 double LP known as *The White Album*, officially titled *The Beatles*, it marked a turning point not only for music history but also for the internal dynamics of the world’s most influential rock band. While the album produced some of the group’s most beloved songs and showcased their creative diversity, the experience of making it was far from joyful—especially for George Harrison.

In interviews and retrospectives, Harrison repeatedly described the making of *The White Album* as one of the darkest, most depressing periods of his life with the band. His frustration stemmed from a combination of personal stagnation, creative repression, and a deteriorating group dynamic that would soon push the Fab Four to the brink of collapse.

In this in-depth feature, we examine why *The White Album* represented such a low point for George Harrison. We explore the tension between the Beatles, Harrison’s evolving spiritual and musical identity, and how an album filled with musical brilliance could emerge from such profound internal strife.

—

### A Fractured Brotherhood: The Beatles in 1968

By 1968, the Beatles had ceased to be the tight-knit brotherhood that had conquered the world just a few years prior. The camaraderie of their early days, defined by late-night Hamburg gigs and cheeky media banter, had been replaced by ego clashes, artistic disputes, and business complications.

Harrison, who had long been perceived as the “quiet Beatle,” began to bristle under the creative shadow cast by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. As Lennon delved deeper into experimental sounds and became increasingly involved with Yoko Ono, and McCartney grew more controlling in the studio, Harrison found himself struggling to assert his creative voice.

In a 1977 interview with Crawdaddy magazine, Harrison recalled:

> “That was the low point in terms of my involvement. Most of the time, I felt like an outsider. I’d write a song, and they’d just kind of nod and move on. It was depressing.”

—

### Mounting Frustration: Harrison’s Fight for Creative Space

By the time *The White Album* sessions began in May 1968 at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios), Harrison had evolved significantly as a songwriter. His compositions were no longer mere filler between Lennon-McCartney masterpieces. Songs like “Taxman” (*Revolver*, 1966) and “Within You Without You” (*Sgt. Pepper*, 1967) showcased a maturing musical intellect and spiritual depth. Yet despite this growth, Harrison continued to struggle for recognition.

He brought several songs to the *White Album* sessions, including “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” “Piggies,” “Long, Long, Long,” and “Savoy Truffle.” All these tracks are now hailed as classic Beatles material. Yet, at the time, Harrison had to fight to even get them recorded.

In one particularly disheartening incident, Harrison was so disappointed by the band’s lukewarm attitude toward “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” that he brought in his friend Eric Clapton to play the searing lead guitar solo that revitalized the track.

> “It was pathetic,” Harrison later said. “Nobody was interested. They were all too busy doing their own little things.”

Clapton’s appearance brought a rare moment of unity to the sessions, as the band temporarily put aside their differences out of respect for the guest musician. But the fact that Harrison needed an outsider to validate his contributions spoke volumes about the toxic studio environment.

—

### The Rise of Individualism: Splintered Creativity

*The White Album* is often seen as a collection of solo projects disguised as a group effort. Each Beatle was moving in a different direction musically, and the album reflects this diversity in tone, genre, and style. McCartney’s “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” had little in common with Lennon’s raw “Yer Blues” or Harrison’s introspective “Long, Long, Long.”

This creative divergence left Harrison feeling creatively isolated. He wasn’t merely fighting for studio time; he was battling an institutional hierarchy that placed Lennon and McCartney at the helm.

> “It became a bit like school,” Harrison would later say. “If you weren’t in with the headmasters, you didn’t get a chance.”

The Beatles’ personal relationships were also fraying. Ringo Starr briefly quit the band during the sessions due to tension, and Lennon’s increasing dependence on Yoko Ono created further complications. Harrison’s once-close friendship with Lennon, in particular, suffered during this period. Their spiritual journeys had diverged—Harrison was committed to Indian philosophy and meditation, while Lennon was becoming more politically and artistically radical.

—

### A Spiritual Awakening Amid Studio Disillusionment

While Harrison felt emotionally estranged in the studio, he was simultaneously undergoing a profound spiritual transformation. After studying with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh earlier in 1968, Harrison returned to England more committed than ever to a life of meditation, detachment, and Eastern philosophy.

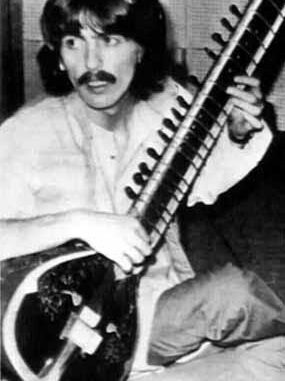

The Beatles’ trip to India was initially meant to bring them peace and clarity, but it also revealed deep differences. Lennon grew disillusioned with the Maharishi. McCartney returned early. Harrison stayed the longest, soaking in sitar lessons, Vedic texts, and quiet introspection. His spiritual growth made the chaos of London’s recording sessions feel especially bleak by comparison.

In Harrison’s mind, the egotism and bitterness in the studio were spiritually corrosive. He later remarked that making *The White Album* felt like “the opposite of everything we learned in India.” For a man trying to live with purpose and humility, the petty bickering and creative gatekeeping of the Beatles’ recording sessions were not just frustrating—they were soul-crushing.

—

### The Rejection of His Work Outside the Beatles

During this time, Harrison began to experiment with solo work outside the band. He composed the instrumental soundtrack to the film *Wonderwall*, released in late 1968. The project gave Harrison the freedom he craved—space to explore Indian classical music, experimental sounds, and film scoring.

However, even this endeavor was met with lukewarm interest from the other Beatles. They viewed it as a side project, a hobby, and didn’t fully appreciate its significance to Harrison. The feeling of being creatively stifled only deepened.

It was also during this period that Harrison began collaborating more seriously with musicians outside the Beatles, including Clapton and Bob Dylan. These relationships offered a stark contrast to the suffocating atmosphere at Abbey Road. Clapton, in particular, treated Harrison as an equal, something he rarely experienced within the Beatles hierarchy.

—

### Recording in Isolation: A Metaphor for Disconnection

Technically, *The White Album* was made at a time of innovation and experimentation. The Beatles were among the first to adopt eight-track recording at EMI Studios, and producer George Martin’s absence from some sessions meant the band had more control than ever.

But that freedom often led to chaos. Instead of working as a unified group, the Beatles increasingly recorded separately. Harrison would lay down guitar tracks alone or with a single engineer. Lennon and McCartney would overdub vocals or instruments without informing the others. This siloed approach heightened the sense of emotional disconnection for Harrison.

The often-cited anecdote about Lennon recording “Revolution 9” late into the night, with Yoko Ono by his side, while the other Beatles were absent, encapsulates the isolation that defined the *White Album* era. Harrison wasn’t just being excluded from musical decisions—he was physically absent from sessions that no longer required or welcomed his input.

—

### “It Was Tense, It Was Depressing…”

In *Anthology* and other documentaries, Harrison never minced words when describing the *White Album* period.

> “It was tense. It was depressing. There was a lot of bad feeling,” he said. “It wasn’t a fun time. It wasn’t creative in the way it should have been. It was just people trying to outdo each other.”

This tension was evident in the sound of the album—raw, diverse, and at times fragmented. Though the music has since been hailed as some of the most innovative in the Beatles’ discography, it came at a high emotional cost.

—

### Seeds of Departure: Toward a Solo Career

While Harrison would remain with the Beatles until their breakup in 1970, the *White Album* was a tipping point. It was the moment he realized his creative ambitions could not be fulfilled within the band.

In the wake of the album, Harrison began writing more prolifically. He stockpiled songs that would later appear on his landmark 1970 solo album *All Things Must Pass*, including “Isn’t It a Pity” and “Let It Down”—both rejected during Beatles sessions. These weren’t cast-offs; they were masterpieces waiting for a home.

The *White Album* also helped Harrison find his voice—not just as a songwriter, but as an artist who needed to define himself beyond the Beatles’ collective identity.

—

### A Retrospective Legacy

In hindsight, the *White Album* stands as a paradox: a masterpiece born of misery. For George Harrison, it was both a creative awakening and a spiritual low. His contributions—limited though they were compared to Lennon-McCartney—provided some of the album’s emotional core and lyrical depth.

Critics and fans now recognize Harrison’s *White Album* songs as essential pieces of the Beatles’ legacy. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” remains one of the most powerful expressions of vulnerability in the band’s catalog. “Long, Long, Long” is a haunting spiritual whisper. “Savoy Truffle” adds humor and edge.

But at the time, none of that validation existed. Harrison created in the dark, against resistance, fueled by disillusionment.

—

### Conclusion: From Darkness to Independence

The *White Album* wasn’t just the Beatles’ most diverse album—it was also their most divided. For George Harrison, it was a crucible. The experience of making it exposed everything wrong with the band: the egos, the favoritism, the creative bottleneck.

Yet out of that suffering came growth. Harrison would eventually emerge from the Beatles not as an afterthought, but as a formidable solo artist whose spiritual depth and musical range earned him enduring respect.

In that way, *The White Album* may have been Har

rison’s most depressing Beatles experience—but it was also the spark that lit the path to his greatest independence.

Leave a Reply